Take Five #161: How to use the 13 Week Cash Flow Model to survive a cash crunch, and more

Top five must-reads this week in the world of SMB acquisitions and operations

Subscribe to Take Five to get our top 5 quick weekly reads on the world of SMB, M&A, and EtA from the team at Kumo. Kumo aggregates hundreds of thousands of deals into one easy-to-use platform so that you can spend less time sourcing, and more time closing deals.

Take Five is created and sponsored by Kumo, a powerful deal aggregator to help supercharge your deal sourcing at withkumo.com.

What can you do with Kumo?

Browse 120,000+ deals from hundreds of brokers and every major marketplace, with 700+ unique deals added daily.

Save time and stop reviewing duplicate deals. Kumo matches identical deals across hundreds of sources so you can view unique business opportunities, even if they’re slightly different across different websites.

Get a daily email for deals that match your search criteria.

Take Five #161: How to use the 13 Week Cash Flow Model to survive a cash crunch, and more

1. Aligning your skills with the right business minimizes risk, boosts growth potential

Your Edge Isn’t in the CIM

Back to that solar deal.

The reason I didn’t move forward wasn’t because the business didn’t have potential. It was because I wasn’t the person to unlock it.

But someone else could have been. And that’s the point.

When you find a business where your attitude, aptitude, and action align – you are the thing that makes it low risk.

You’re not buying perfection. You’re buying potential – and you’re the one who brings it to life.

That’s where the upside is.

And that’s how you find high returns without taking on unnecessary risk.

Read the rest of Buy Then Build’s article here.

2. 4 reasons why buying a distribution business is better than building one

3. “Brad Jacobs’ Quadrant: How to Evaluate Big, Messy, Worthwhile Bets”

Brad Jacobs evaluates opportunities along two critical axes: deal size and operational complexity. These two variables form the foundation of his investment philosophy—not because they’re novel, but because of how he interprets them through a systems lens.

Deal size refers to the total revenue base or the scope of economic opportunity a business presents. It answers a central question: If we get this right, how big can this become? Size matters not because it guarantees success, but because it creates room for professional management, margin expansion, and reinvestment. Larger businesses allow for deeper leadership benches, more meaningful systems, and a structurally higher ceiling on growth. A $5 million revenue business with 20% EBITDA may look appealing, but a $50 million revenue business at break-even—if fixable—offers a much more scalable platform.

The second axis is mess, which Jacobs uses as shorthand for deal risk—the operational, cultural, and structural issues that make a company difficult to run. This includes everything from founder-dependence and outdated systems to poor financial visibility, inconsistent service quality, or missing leadership layers. Mess, in this context, isn’t a disqualifier—it’s a constraint. And like all constraints, it can either block growth or become the raw material for transformation. Jacobs’ insight is that not all mess is fatal. Some of it is cosmetic. Some of it is solvable. The key is distinguishing between the two.

Find the rest of Mindful Capital’s post here.

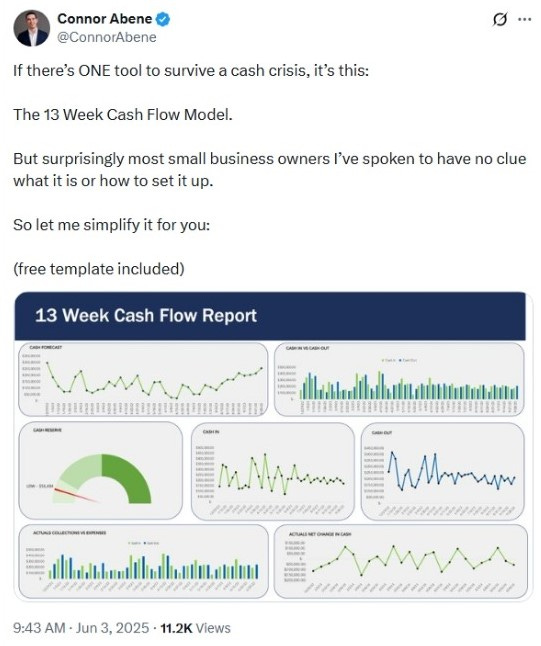

4. How to use the 13 Week Cash Flow Model to survive a cash crunch (includes template)

5. Earnout structures for SMB deals explained

2. Reverse Earnout with Escrow Holdback

A reverse earnout with escrow holdback flips the script on the traditional earnout model. Instead of tying part of the purchase price to future performance, the buyer pays the entire amount upfront - including what would typically be the earnout portion. If the business underperforms, the buyer can recover a portion of that payment. This setup shifts the risk to the seller while ensuring they receive immediate cash flow - unlike a traditional earnout.

Mechanics

Here’s how it works: the buyer pays the full purchase price at closing, but a portion is held in escrow or structured as an adjustable promissory note. If the business doesn’t hit the agreed-upon performance targets, the seller must refund part of the purchase price. The escrow holdback is usually a percentage of the total purchase price. For instance, data from 2014 shows that, on average, 9.14% of the purchase price was placed in escrow, with a median of 7.5%. Timing is critical here - capital losses can only be carried back for three years. If the refund happens after that window, the seller may face a capital loss that can’t be offset.

When to Use

This structure works well when buyers want to close deals quickly while still protecting themselves from potential underperformance. It’s particularly useful in asset sales or situations where traditional earnouts might feel too restrictive. Sellers who are confident in their projections and prefer receiving full payment upfront are likely to find this arrangement appealing.

Loved what you read? Subscribe to Take Five to get our top quick reads every week from the team at Kumo. Kumo aggregates thousands of sources into one easy-to-use platform so that you can spend less time sourcing, and more time closing deals.